Fundamentals of Photography: Mastering the Exposure Triangle to Improve your Photography

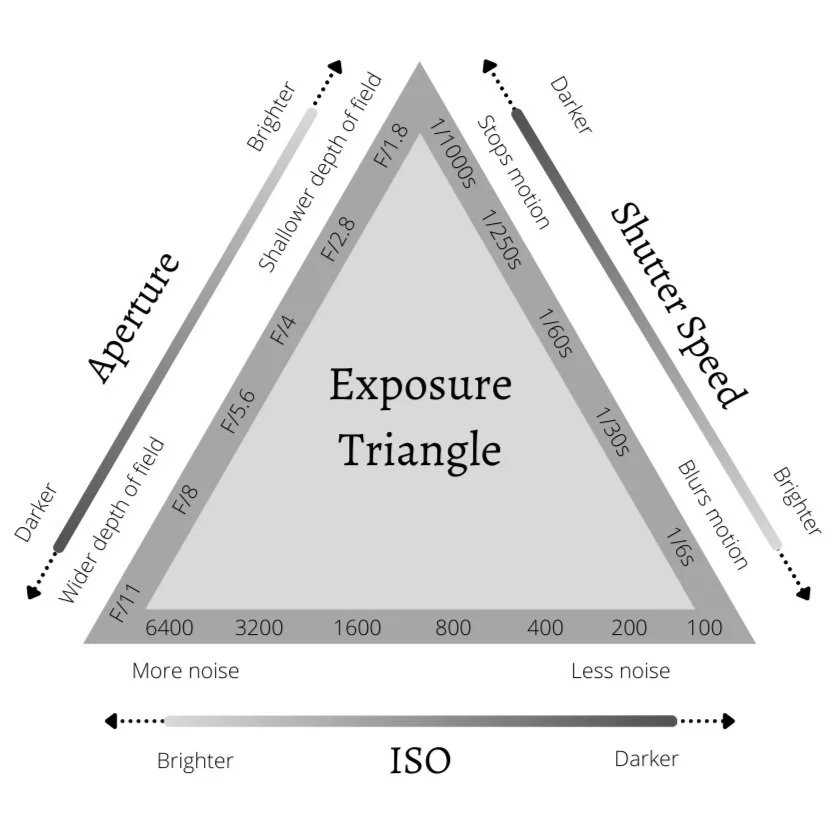

The exposure triangle - one thing that seems to crop up everywhere when you Google ‘basics of photography’. In its most basic definition, exposure in photography is the amount of light that reaches the camera sensor (or film), and is responsible for the brightness of your photos. Each of the three parts of the exposure triangle contribute to the overall exposure of your image in different ways.

Understanding of the exposure triangle means that you, or the technology in your camera, can pick the right settings at the right time for the right job. This will be a straightforward explanation of what the three parts of the exposure triangle are, and how you can use this knowledge to your advantage when taking photos. There will be more focussed and in-depth articles on each of the three parts of the exposure triangle in the future, but for now let’s look at the basics.

How Does a Camera Work?

A modern camera, at its most basic level, takes the light bouncing you and focusses that light through a lens on to a light detecting surface, be that photographic film or an electronic camera sensor, to give you your image. You can change the end result of your image in many ways, such as using different lenses or focal lengths, as well as applying various changes in post-processing to edit your image. However, it is not possible to take a photo without the use of the exposure triangle. In this article we’ll look into the roles of the 3 parts of the exposure triangle and how they affect what the image you take will look like. Having a solid understanding of the exposure triangle means you can anticipate how an image will look before pressing the shutter button, and hopefully save you some time by not having to take hundreds of photos of the same subject to get the desired result (as I certainly did when starting out!).

Parts of the Exposure Triangle

The exposure triangle (or photographer’s triangle) is made up of three parts:

1. Shutter speed

2. Aperture

3. ISO

By changing these 3 settings, you change the way light interacts with the sensor or film and the overall exposure (bright vs dark). Shutter speed and aperture both affect physical properties within the camera and how much light can enter the camera to hit the sensor. ISO on the other hand affects how sensitive the sensor/film is to the light that hits it.

These settings also impact on depth of field, motion and noise, and we’ll go through how this happens in the next sections.

Any diagram of the exposure triangle can certainly look overwhelming, but below I’ve broken it down into each component which will hopefully help make sense of it all.

Stop!

If you read about or watch videos on photography you will frequently hear the term stop used in terms of exposure and settings, and it can certainly get confusing. In simple terms, a stop is a relative term for measuring exposure, or the amount of light. If you increase exposure by one stop, you have doubled the amount of light that hits the sensor. Similarly, if you decrease exposure by one stop, you halve the amount of light that hits the sensor. We’ll go through this in more detail in the separate articles on shutter speed, aperture and ISO as it’s easier to get your head round when looking specifically at each area.

Shutter Speed

Photo taken with a shutter speed of 1s to smooth the movement of the water.

Let’s start with shutter speed. Every time you press the shutter button to take a photo, the camera shutter will open for a certain period of time, known as the shutter speed, while the camera takes the photo. In other words, the shutter speed is the length of time that the camera shut stays open whenever you take a photo.

In terms of exposure, the longer the camera shutter is open (ie a longer shutter speed), the brighter the image will be. Vice versa, the shorter the shutter speed the darker the image will be.

Shutter speed is measured in fractions of a second or seconds and can include speeds like:

· 1s

· 1/25s

· 1/250s

· 1/1000s

The larger the second number, the shorter the shutter speed, as these are fractions of a second. For example, 1/25s is one twenty-fifth of a second, compared to 1/1000s being one thousandth of a second. Shutter speed can be hugely varied, going up to long exposures of several minutes (doing things like night-time or astro photography), down to fractions of a millisecond (1/4000s).

The other main thing that shutter speed affects in your image is motion. A faster shutter speed, or a shorter time the camera shutter is open, means that motion is frozen. When photographing subjects that are moving quickly, such as a car on a racetrack or water down a waterfall, a faster shutter speed (such as 1/2000s) will allow you to freeze that subject. This means you will be able to see the expression on the driver’s face or the shape of water droplets in that split second. In contrast, a slower shutter speed (such as 1/6s) will produce motion blur, where the car or rushing water will be blurred and lose detail.

The wrong choice of shutter speed is a really common cause of having blurred photos, so it is essential to get an understanding of what shutter speed will stop motion in a particular subject. For example, preventing blurry images of trees swaying in a light breeze will need a different shutter speed to a car on a racetrack. Be sure to experiment with your camera with different subjects to really get to grips with what shutter speed to choose for the right situation.

Aperture

The next part of the exposure triangle is aperture. Aperture refers to the opening through which light travels to enter your camera. When changing the aperture you are changing the diameter of the lens’s diaphragm (opening). A wider aperture (bigger diameter) means more light can enter the camera and hit the sensor and give a brighter image. In contrast, a narrower aperture (smaller diameter) means less light can enter the camera and gives you a darker image.

Aperture is specified as an f-stop or f-number such as f/8, f/4 or f/2.8. Somewhat counterintuitively (although it does make sense with the physics involved), the larger the f-stop, the narrower the aperture, as shown in the diagram. For a full explanation of aperture please go to the specific article here. Each stop indicates the fact that the diameter of the aperture has halved. Going from f/4 to f/5.6 or from f/5.6 to f/8 means that the diameter has halved. It can get confusing given the fact that a larger f-stop means a narrower aperture, but with time and practice this becomes natural.

In terms of exposure, you can use the aperture to achieve the desired brightness of the image. For example, when shooting night time or astro photography, using a really wide aperture (eg f/2.8) means the camera lets in as much light as possible to capture the stars. In contrast, in a very bright environment or when shooting at the sun, a narrower aperture (eg f/11) will help to darken the image and stop it being over-exposed.

The other effect of changing aperture is to change the depth of field of an image. Depth of field essentially means how much of your photo will appear in focus and sharp. It can be defined as the distance between the nearest and farthest objects in an image that are acceptably sharp. A wider aperture (and low f-stop, such as f/2.8) gives you a shallow depth of field. This means that only a small range of your image will be sharp and in focus. This is commonly used in portrait or macro photography, where you want the image to be focussing only on your subject. Your main subject, be that a person, animal or flower, will be in focus but the rest of the image will appear blurred and give you that wonderful bokeh effect.

Conversely, when you want as much of your image as possible to be in focus you’ll need to use a smaller aperture (larger f-stop, such as f/11). This gives you a deeper depth of field and means you can keep both foreground and background of your photos in focus and sharp.

Again, by experimenting with your own camera taking photos of the same subject using different apertures you will really see the difference this makes.

ISO

The ISO refers to the sensitivity of your camera’s sensor. Despite looking like it should be an acronym for something, it’s not. The “International Organisation for Standardisation” are a group that create technology and product standards, and decided on different standards of camera film and sensor sensitivity. However, as they have a different name in different languages, the International Organisation for Standardisation decided to use the term ‘ISO’ (not an acronym) to refer to the sensitivity of camera film and camera sensors.

The digital image made by your camera is dictated by how much light hits each part of the sensor. Each pixel in the sensor (for example 24 million pixels in a 24MP camera) detects how much light hits it in the way of photons, and the camera pieces together the information from each of the pixels to generate the overall image. A low ISO, or low sensitivity to light, means more light has to hit the sensor to produce the same image than at a higher ISO, or higher sensitivity to light.

You will see ISO settings like:

· 100

· 400

· 1600

· 6400

The range of ISO available to you will depend on the camera you use. Most cameras start with ISO 100 as the lowest, and go up to the tens of thousands (eg ISO 25600). When using the same shutter speed and aperture, a higher ISO means the image will be brighter, and a lower ISO means the image will be darker.

However, using a higher ISO will cause there to be more noise in your image, giving it the grainy look we associate with very old film photography. As a result, it is generally best to keep the ISO as low as possible in order to reduce noise in your photos. Sometimes it can be impossible to get an adequately exposed image without increasing the ISO, but always be aware that noise and the graininess of your photos will increase too.

How to Use the Exposure Triangle in Your Photography

Image taken at 18mm, ISO 100, f/13, 4s exposure.

So now we’ve been through what the three parts of the exposure triangle are, what does that mean for my photography?

As mentioned above, solid understanding of how these 3 parts interact will mean you can choose the right settings for the right job. However, you also need to understand that it is the combination of all three factors that will dictate the overall exposure of your image.

As an example, let’s say you’re taking a photo of a beach. You want to use a slightly longer shutter speed to get smooth, silky looking effect of the waves, so we set a long shutter speed. There’s also some nice rocks in the foreground so we want to make sure we have a wide depth of field so everything is in focus, so we set the aperture to f/13. It’s fairly bright, so the exposure looks good using ISO 100 (the lowest setting).

Image taken at 50mm, ISO 100, f/1.8, 1/2500s exposure.

In contrast, let’s say we want to take a close up macro photo of a nice flower. We the emphasis to be on the flower itself, so we want to use a very narrow depth of field and get that bokeh effect blurring the background. As a result, we use a really wide aperture of f/1.8. Because this wide aperture will be letting in loads of light we need to make sure we don’t overexpose the image, and use the other parts of the exposure triangle to darken it. We use ISO 100 to make the sensor the least sensitive to light and has the least noise. We also then use a really short shutter speed, so even though the aperture is huge there’s only a fraction of a second for light to get through it, so we use a shutter speed of 1/2500s.

Hopefully from these examples it’s starting to make sense how the three parts of the exposure triangle are used both for controlling the exposure of an image as well as the secondary effects of each (motion/depth of field/noise).

In the first instance, make of use the technology in your camera to help. That’s what it’s there for! Start off with the auto mode on your camera and take pictures of whatever you like, but notice what settings your camera has used in each scenario and learn from this for the future. It’s also really helpful to use the aperture-priority and shutter-priority modes as well. These are essentially a step up from the fully auto mode, and give you control over one of the settings while the camera controls the rest. If you want a photo of smooth water, use shutter-priority to set the shutter speed to 1/2s, take note of what aperture and ISO the camera has used to make sure the image isn’t over or under-exposed. Similarly, if you want a nice portrait with a bokeh background, use aperture priority and set the aperture nice and wide (such as f/2.8) and notice what shutter speed and ISO the camera uses to get a good exposure.

It takes a long time to really master the exposure triangle, and I’m certainly still learning 5 years later, but it really is a key part of every photo you take. You can be in the most beautiful place in the world with a perfect composition, but take a heap of badly exposed, blurry photos if you don’t have a good understanding of how the exposure triangle works. I’m sure any photographer will tell you the same, but honestly with time and practice choosing all of these settings will become second nature and really will give you the ultimate control over your photos.